Medford police chief calls bodycam launch a success

But he also admits there’s been a learning curve for officers, and more training is needed

Police officers made over 31,000 videos, of which 1,883 were related to arrests, with body-worn camera (BWC) equipment in 2024, according to the annual surveillance report presented to the City Council’s Public Health and Community Safety Committee.

“I have to say, we find the program to be successful,” said Police Chief Jack Buckley in his presentation on May 7. “It is accomplishing all of the objectives that we as a police department wanted to, want to obtain.”

But that doesn’t mean there weren’t some obstacles.

Setting the stage

Police launched a body-worn cameral pilot program in 2023. In 2024 the cameras became part of the job and all officers were required to wear and use them in accordance with city policy. According to the report, Buckley said because it’s new technology this first year was treated much like a pilot program where minor violations, not criminal in nature, were managed with additional training and counseling, as opposed to formal discipline.

Infractions were discovered during audits, in which three videos of each officer were viewed to ensure they were complying with the policy. A separate access audit was also performed to make sure supervisors were the only ones actually viewing the videos.

Reactions

City Councilor Emily Lazzaro said she noticed two things in the report; that it seemed difficult for every officer to remember to take their camera with them and that not everyone was advising people in their vicinity that they were being recorded.

“They are two shortcomings that we want to improve on,” Buckley admitted.

He said the cameras are a habit that for some has yet to be formed. But, he said, Lt. Pat Duffy, who is commander of the body-worn camera unit, does “advise, advise, advise” those who do forget.

City Councilor Kit Collins was also concerned with the number of officers failing to announce that an incident was being recorded.

“That jumps out to me as the biggest red flag,” she said. “That's a pretty high number to be deviating from the policy.”

She asked Buckley how he planned to get that number up from 33% to 99%, but Duffy noted that the statistic could also be misleading. According to Duffy, only the first officer on the scene has to announce that people are being recorded. He said they had no way of knowing if the officers they viewed in the random video audit were first on the scene or fourth. And he doesn’t have the time or the resources to look at all the videos attached to each incident “just to check that person off.”

Duffy also noted that if anyone at a scene requests the cameras be turned off, officers make a note of the request then oblige and turn the cameras off, unless they are about to make an arrest.

“We have not had, to my knowledge, one complaint where someone said ‘you were recording me and I didn't know about it,’” he said.

Buckley also pointed out that there have been no complaints filed regarding the surveillance technology on the whole.

Duffy said there were times when officers forgot to turn their cameras on or turned them on late.

“Again, it's muscle memory,” he said. “I don't see any ill intent on someone hiding anything but trying not to record. It's just they're not used to it yet.”

When Councilor Anna Callahan asked how Medford stacked up against other cities using body-worn cameras, Duffy said most departments he’s spoken with don’t do audits.

“I will say we’re probably leading the pack as far as doing audits,” he said.

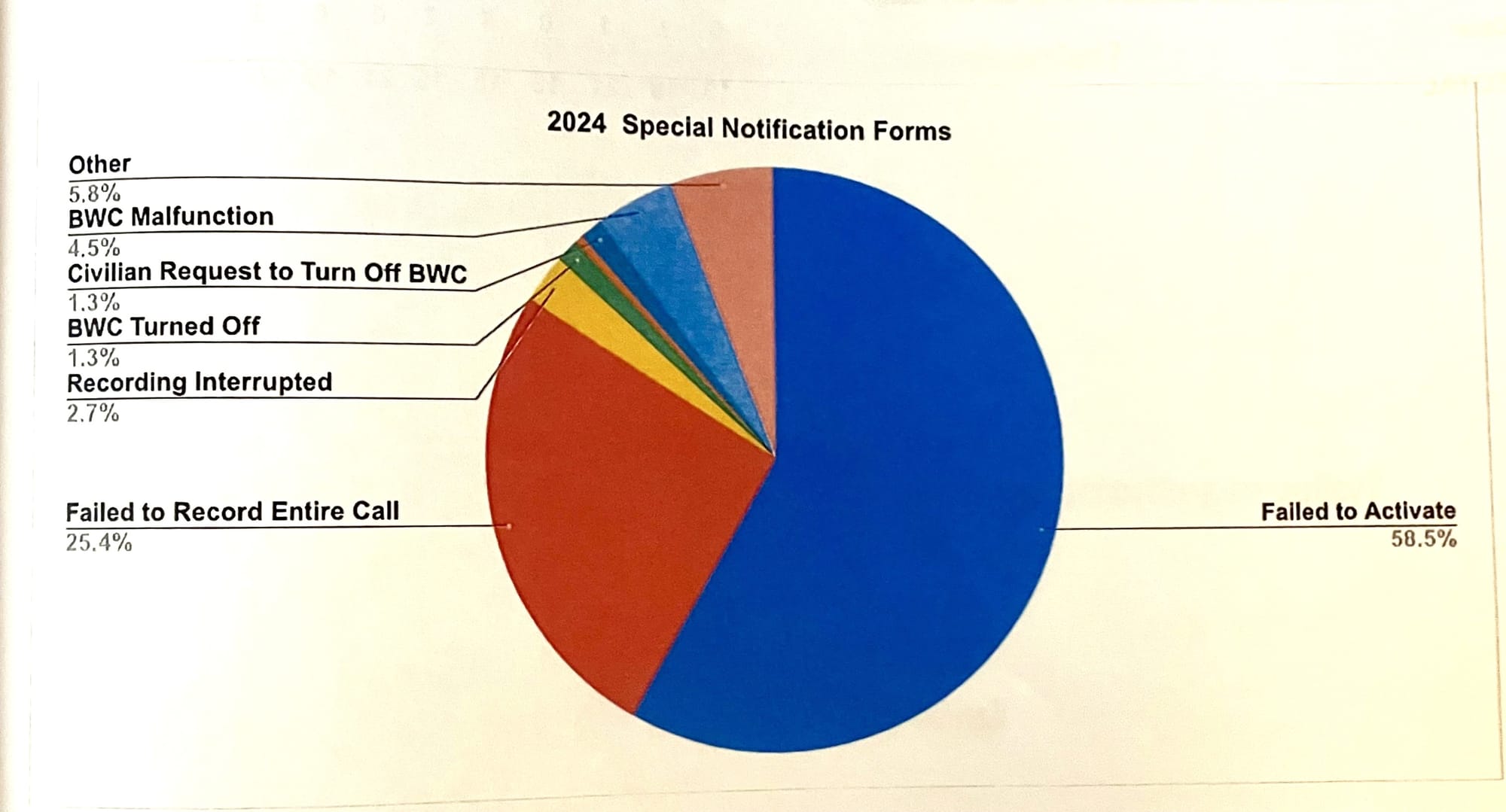

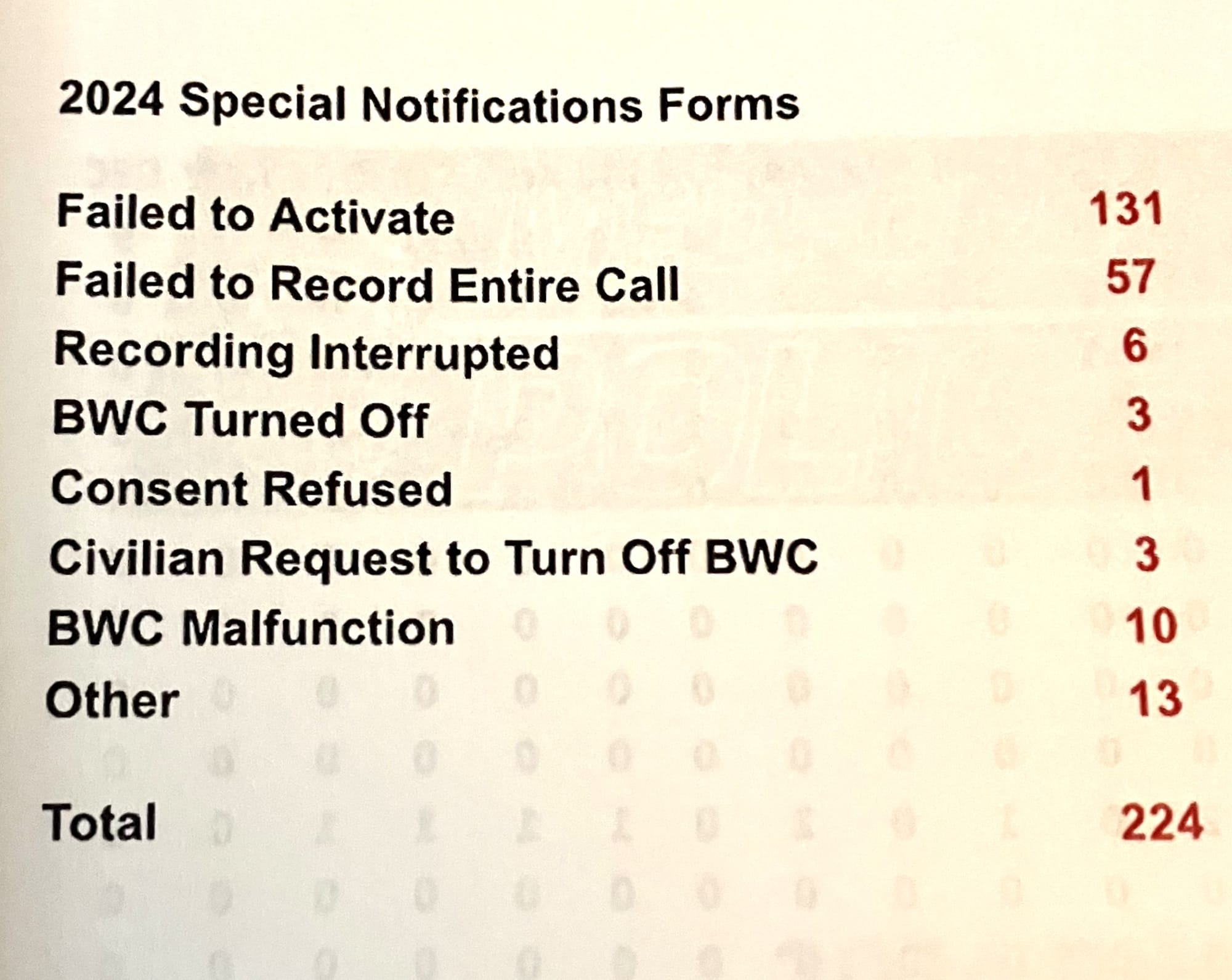

Matt Leming wondered about the reported 131 officers who failed to activate their cameras.

Duffy said officers self-report when they fail to activate their camera and more often than not it is the patrol division making the infractions. He said often they are running out to back up their partner and forget to grab their camera, and it’s more important to back up their partner than go back for the camera.

“There's no one person that's forgetting 10, 12, 15 times over the course of the year,” he said. “That would be a red flag for us.”

Buckley said it’s also important to note that they respond to “thousands and thousands and thousands of calls each month.”

Also having their say on the report were representatives from Medford People Power, an independent organization that generally aligns itself with the values of the American Civil Liberties Union and works with local leaders. They were concerned that they didn’t have proper time to review the report prior to the presentation and they wondered how use of the cameras played out in terms of race and ethnicity and why people had to pay to have a video redacted.

“We don't have a breakdown of the race, ethnicity and the instances when the camera was not turned on versus when it was on,” said Elizabeth Burke. “I understand that the audit and the focus on training is to have the officers turn on the camera every time it is required, we would like to see those numbers improve over time with training and be assured that there is no bias in their use.”

Lazzaro said it was council’s fault the group didn’t receive the report in a timely manner. Although police were a month late in filing the report, Lazzaro said she in turn forgot to send it to Medford People Power.

Jean Zotter also wondered why residents have to pay to have videos redacted. She worries that it sets up a two-tier system where people that can’t afford to pay don’t get to protect their privacy while those who can pay do.

Videos can be redacted for a variety of reasons, including protecting victims, witnesses, juveniles, medical information, undercover officers and the average citizen who is not a suspect or person of interest in a case, to name a few.

Public records officer Lt. Joe Casey said state law allows them to charge $25 per hour for redaction beyond the first two hours. Casey said anytime they’re going to charge for a redaction they file a petition with the supervisor of records, and they decide whether or not they’re authorized to charge.

Collins suggested that next year's report be a bit broader and include data to back up “what we know about the good faith intent of this equipment and the people using them.”

Lazzaro thanked Buckley and Duffy for their time.

“It's a new technology," she said. "It's a new ordinance with reporting the requirement, and it's our first time having access to this level of data, and we're also learning about how you process the data. So, we've had a lot of questions today, and I appreciate your comprehensive, thorough responses.”