New book examines Paul Revere’s ride, Medford’s place in history

A new book about Paul Revere's famous ride, includes his travels through Medford.

By Rich Tenorio

When Paul Revere got on a borrowed horse to warn the American colonists that British troops were on the march, he knew who to contact: 36-year-old patriot Isaac Hall.

A distillery owner, husband and father of two, Hall was also an officer in the Medford Minutemen, part of the legendary colonial militia who could be ready in 60 seconds.

Revere did not stop after passing the word to Hall during his famed midnight ride on the evening of April 18-19, 1775. In Medford Square, he encountered a fellow rider on horseback: Dr. Martin Herrick. Revere trusted Herrick with the intel and the doctor spread the word as far as Lynnfield and Reading.

Author Kostya Kennedy, right, has written ‘The Ride: Paul Revere and the Night that Saved America.’ COURTESY PHOTO OF AUTHOR/AMY LEVINE-KENNEDY

This is part of the narrative of a new book about Revere’s ride during its 250th anniversary year – “The Ride: Paul Revere and the Night that Saved America” by Kostya Kennedy. The author of three award-winning books on baseball history, and an executive at Dotdash Media, Kennedy now turns his eye to a pivotal moment on the eve of the American Revolution.

“Revere knew what time it was in his life,” Kennedy said. “He knew the critical moment in his own life. He clearly knew what time the young rebellion was getting underway. His number was called. He so extraordinarily met the moment.”

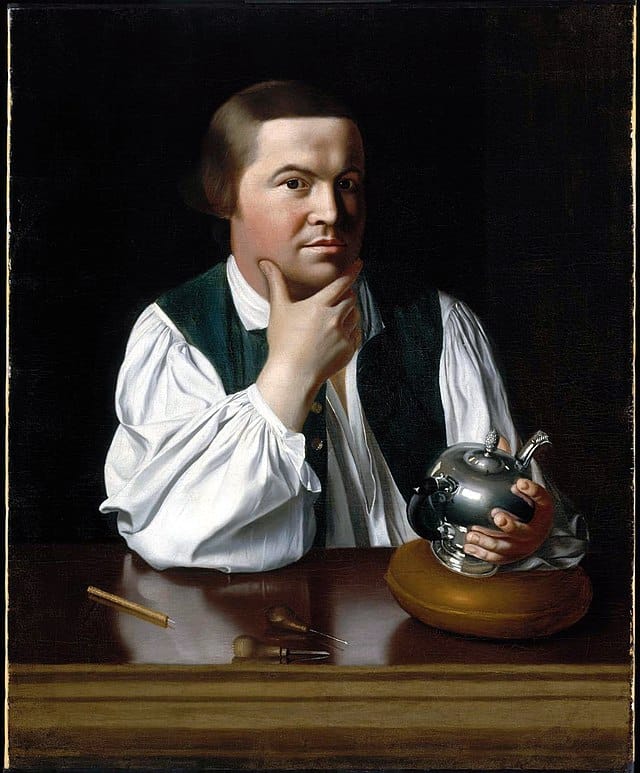

Revere had recently turned 40 when he made his midnight ride on a mare named Brown Beauty. A patriot operative living in the North End of Boston, he was close to revolutionary leaders such as Samuel Adams, John Adams, John Hancock, and Dr. Joseph Warren. He was the man for the job, having already undertaken much longer rides to New York and Philadelphia for the patriot cause.

Kennedy mentioned Revere’s working-class resume: He was a silversmith, engraver – and self-trained dentist.

“He was sort of this blue-collar everyman, in a way some of the other leaders were not,” Kennedy said.

To research the book, the author visited many archival resources, such as the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Lexington Historical Society, the Portsmouth Athenaeum and the New Hampshire Historical Society, as well as multiple libraries.

“I was combing through the documents, looking for anything specifically related to Revere and that night,” Kennedy said. “I tried to do some hands-on research – I climbed to the top of the Old North Church.”

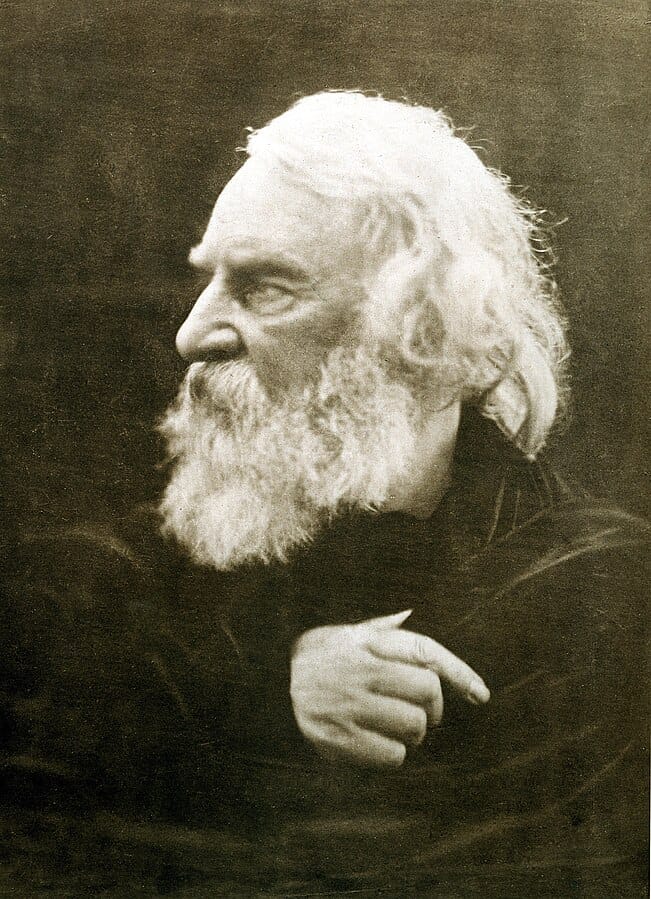

The famed Boston church was the site where Revere watched to see how many lanterns would be hung, “one if by land, two if by sea” – indicative of the route the British soldiers would take, and part of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s classic 1860 poem “Paul Revere’s Ride.”

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s classic poem ‘Paul Revere’s Ride,’ was written in 1860. COURTESY PHOTOS/WIKIPEDIA

Kennedy remembers being read the poem from a book when he was nine or 10 years old. The book had no illustrations, so he imagined the story in his head.

“It’s a wonderful poem that’s stayed with us,” he said. “The poem, in general, is accurate. The spirit of it, the essence of it, most of the facts are true.” And, he added, “The poem, if anything, rose in stature in my mind.”

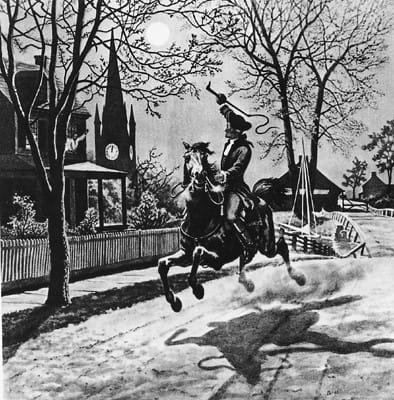

“Paul Revere’s Ride” mentions some familiar local names – the Mystic River, Middlesex County and Medford itself, with its subject riding through at midnight: “It was twelve by the village clock, / When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.”

In “The Ride,” Revere himself is quoted to illuminate that night. At the outset, he had a brush with two British soldiers. Dodging them meant doubling back and taking a longer route. Once he crossed the Mystic into Medford, he alerted Hall: “I awaked the captain of the Minutemen.”

The book shows Revere riding through both Medford and neighboring Arlington – which was called Menotomy back then. (In Medford, Revere rode along High Street, up Rock Hill, and past the Medford Meeting House.) Each town consisted of between 800 to 900 inhabitants, according to the author.

“Delivering the alarm did not in each case take much time, didn’t much slow Revere on his intended path,” Kennedy writes. “He spoke directly and firmly, and his words came as tinder to a wanting flame. The Patriots he met were ready to act.”

Kennedy told Gotta Know Medford that this action was a monumental undertaking: “He would show up to the door and say ‘get your fowling piece to confront the British, the most powerful, best-funded army in the world.’”

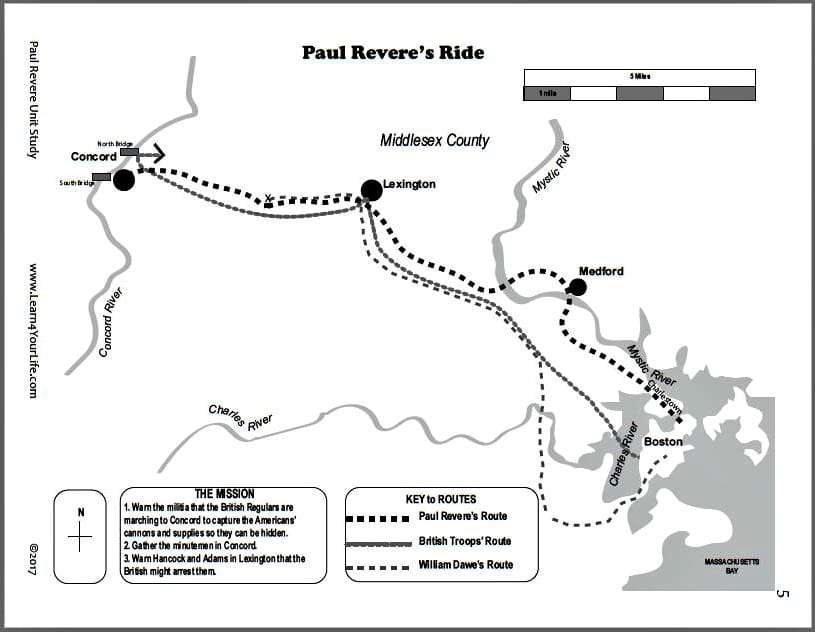

Other riders joined Revere in spreading the word – including William Dawes, whose route took him through Cambridge before connecting with Revere in Lexington; and Dr. Samuel Prescott, the lone member of the trio who made it to Concord, where the British had intended to seize patriot military stores.

Revere, Dawes and Prescott had all been captured en route to Concord. Each used their wits to escape separately; Revere was the last of the three to do so. He went back to Lexington, where he joined patriot leaders Samuel Adams and Hancock. As the British arrived in Lexington, Revere left on yet another secret mission. The first shots of the Revolution were fired that day, arguably set in motion by the famed midnight rider.

“We look at history, all history, as inevitable,” Kennedy said. “Things could have been very different if Revere had not had the success he had on that night. The whole shape of the start of the Revolution, the Revolution itself, might look very different.”