Juneteenth hits close to home with Medford’s Royall House

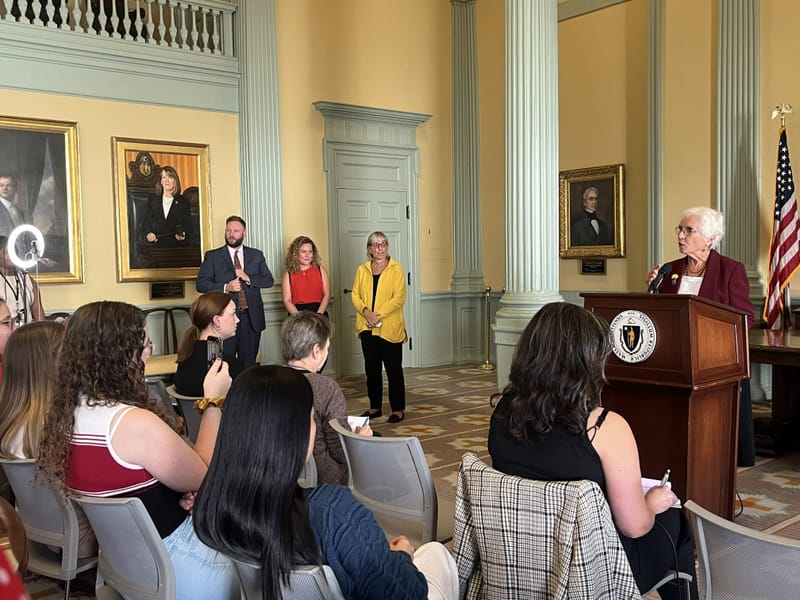

Kyera Singleton, executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters, spoke at the Cambridge Public Library about the history of the oldest extant slave quarters in the North.

By Rich Tenorio

Despite popular perceptions of Massachusetts as the Cradle of Liberty in the 18th century and a center of abolitionism in the 19th century, the history of New England also includes slavery – with a connection to Medford.

That was a takeaway from “Remembering Hard Histories: Slavery in New England,” a June 11 talk at the Cambridge Public Library by Kyera Singleton, executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters, which she described as the oldest extant slave quarters in the North.

“This is in the middle of Medford,” Singleton told an audience of 15 to 20 people. “When you think of a slave quarters, you do not think of Medford, Massachusetts. You might think Mississippi or Georgia.”

The talk took place just over a week before the Juneteenth holiday, which commemorates the end of slavery in the U.S. at the close of the Civil War in 1865. This month, the commonwealth continues to mark the 250th anniversary of the start of the American Revolution.

Singleton’s talk aimed to remedy historical memory: Slavery existed in Massachusetts well into the Revolution, and although slavery has been more widely associated with the South, it existed in Massachusetts into the late 18th century.

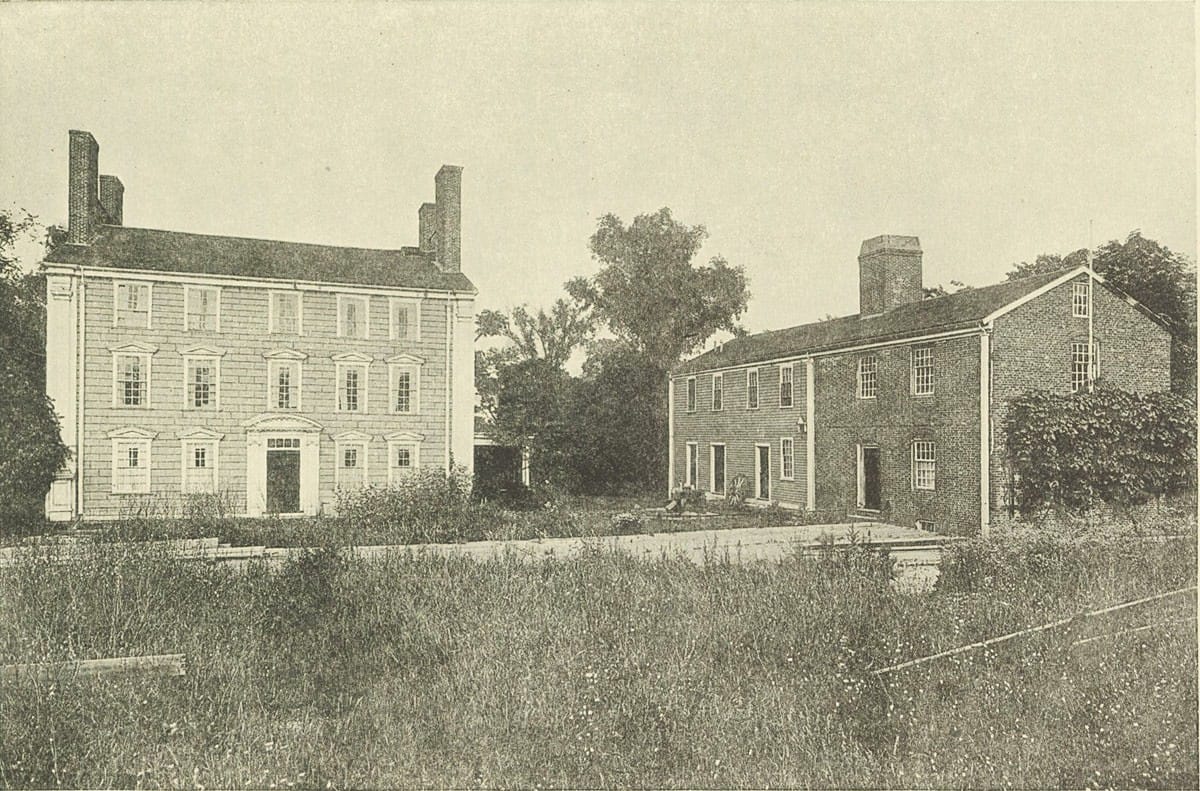

In 1737, the wealthy white Royall family arrived in Massachusetts from another British colony, the Caribbean island of Antigua. The family established a plantation in Medford and would become known for helping found Harvard Law School. Between 1737 to the onset of the American Revolution, the family maintained its fortune through about 60 Black enslaved people.

The narrative of slavery in New England goes beyond the Royalls: The first enslaved people arrived in Massachusetts in 1638, on the slave ship Desire, according to the talk. Native Americans in New England were enslaved by British colonists who traded them for enslaved Africans.

By the 18th century, enslaved people represented 12% of Boston’s population, over 25% of Rhode Island’s population and 4% of New Englanders.

Singleton – a native of Camden, N.J., who received a Ph.D. in American culture from the University of Michigan-Ann Arbor – became executive director of the Royall House and Slave Quarters around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter protests.

As she recalled, a group of protestors marched to the site, outraged that a former slave quarters still existed in Medford. She spoke with them – a peaceful exchange that resulted in the protesters leaving. Yet Singleton felt that more needed to be done to educate the community about the site.

For Singleton, it came down to “how we make this history accessible. People have to understand, it’s not a Confederate monument, it’s not an ode to slavery … It’s actually a site of memory.”

She made a contemporary reference to the demonstrations against the Trump Administration deporting undocumented migrants – demonstrations that have prompted a crackdown from federal authorities: “In the midst of the protests happening in Los Angeles, I’m haunted by how history consistently repeats itself. What is the role of a museum like the Royall House and Slave Quarters?”

From a stage in the library auditorium, Singleton discussed the enslaved Blacks – men, women and children – who once lived at the plantation, which at one point spanned 500 acres across South Medford.

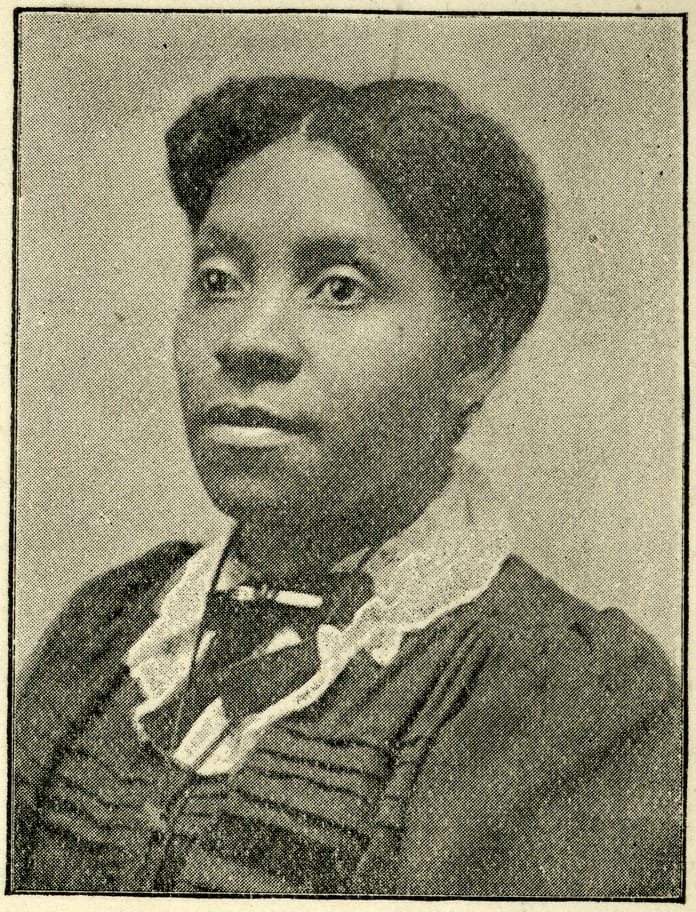

They included Belinda Sutton, a Black woman who petitioned the state Legislature for payment for her labor as an enslaved person after Massachusetts banned slavery in the late 19th century.

Sutton’s actions initially brought a positive result: The legislature agreed that she was owed an annual pension. Yet Singleton noted that Sutton only received two payments, had an ailing daughter to support, and continued to petition the legislature for the balance over the rest of her life.

“Everyone wants to hear a feel-good story,” Singleton said. “No one wants to hear a story in which she keeps petitioning, she’s in poverty, she’s in need of money, she cannot feed herself. No one wants that story.”

During the talk, the names of Sutton and other enslaved people at the Royall House and Slave Quarters were shown on a screen above the stage. Singleton also showed images of the structure and contrasted the respective spaces for wealthy free whites and enslaved Blacks.

“There were two staircases for the Royalls and enslaved people,” she said. “One was quite safe, one was treacherous.”

The environs of Medford limited chances for enslaved Blacks to escape, according to Singleton. In the 18th century, she said, Medford was not a densely populated urban area, but a swampy, rural and quiet town on the Mystic River – making it an attractive summer home for wealthy white enslavers from Boston.

With relatively few residents in Medford compared to Boston, enslaved people who escaped were likely to be noticed, Singleton said.

Nevertheless, the talk showed how enslaved people resisted the oppressive system upheld by the Royalls and others.

Resistance included “everyday ways often overlooked,” Singleton said. “They sometimes broke tools or absconded into the woods for two to three days … At the same time, they would get married and build families, even though forced family separation was part of slavery.

“They did run away, they did fight back,” she said. “Sometimes they were successful, sometimes they weren’t.”

Singleton hopes to continue to impart lessons from the site to educate visitors about both the past and present.

“If you have not been to the museum, I hope you will come to see it, to experience it,” Singleton told the audience.